“All wildlife filming engenders encounters with weird and wonderful animals and plants. It all requires some familiarity with the creatures, some knowledge of their habits and behaviour, some appreciation of the environment in which they live, usually a disproportionate amount of patience and always, but always, a huge dollop of luck. What one tends to forget is one other ingredient, and that is an invariable element of surprise.

Early in the new year, back in 1985, I was alone on Lizard Island, awaiting the arrival of my colleague from OSF, as well as looking forward to Roger Steene joining us for a couple of weeks. Before either arrived, I was alone and enjoying some very calm, fine weather, and intent on searching a coastal stretch a mile or two from the station. Named Crystal Beach, it was storm beach, meaning one that collected interesting flotsam when southerly storms battered the island, and it was as white as snow, hence the name, “Crystal”, and it was half a mile long, dead straight, aback a coral shelf that extended up to two hundred yards seaward.

To its north and south, lay similar rocky promontories that helped funnel incoming storms straight onto the beach. It tended to be little visited by the research students, because it was shallow and a bit boring. I kept a periodic watch on it, because it often collected interesting artefacts, like Nautilus shells, fishing trawl net floats and various dead fish.

So, one fine day I set forth to investigate the full length of this pleasant beach. I moored at the southern end, wandered slowly down the full length, and back again. I kept back from the water because past experience had taught me that large rays frequented this beach, and a vague plan was building in my mind to see if I could approach one close enough to see it feeding. These rays were notoriously skittish, frantically flapping away across the coral platform, long before you ever came close, so somehow I needed to develop a methodology that did not freak them out.

My walk, gave me the time to plan how I was going to attempt it. Accordingly, I kept well inshore, on my return walk. I slipped quietly into the boat to retrieve snorkel, fins, weight belt, camera and facemask. I eased myself into the water, floated face down, selected a depth such that I did not disturb the bottom, but shallow enough that I could touch the sandy bottom with my finger tips. Using nothing other than finger power, I began the slowest, longest glide down that half mile beach, ever performed. It was a snail’s pace.

Sure enough, ahead I soon saw the cloudy disturbance that indicated that I was approaching a feeding ray. Most are bottom feeders, blowing a jet of water out, then sucking in water, sand, and burrowing sand dwellers, like shellfish, brittle stars, Sand Dollars, segmented worms etc which they filter out and swallow whole.

As I got nearer, I realized the ray was facing away from me. That was lucky. Surely I could get that much closer. More finger tip gliding. Not the slightest disturbance from me. It took twenty patient minutes, but by the time my fingers were beginning to think of cramping, I was only six or seven feet from “Reggie Ray”.

For nearly an hour I studied him to my heart’s content, as he dug feeding depression after feeding depression along the beach, all within forty feet of the breaking surf. It was a wonderful experience, and I returned to base feeling both pleased and privileged. The next day, I repeated the study with as satisfactory results.

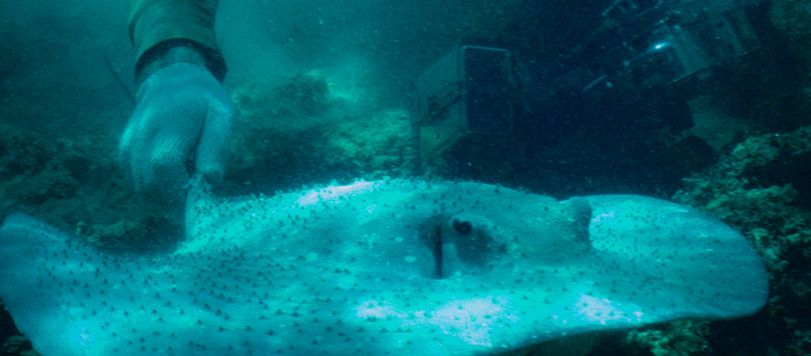

The day after that, Roger arrived. I told him of the experience, and we decided to see if we could do the same the third day. Rog was always game for these sort of patient encounters, and that is why he is one of the very best in his field of underwater marine close up photography. Weather was still fine, and we did exactly as I had done on the previous two days. What we had not expected was what happened next. We got so close that we were literally touching Reggie, and he seemed not to care one little bit. He became so used to us that we each tried gently to move him.

Ultimately, we found that we could gently grasp him at the base of his substantial tail, and nudge him forward to a new, undisturbed patch of sand to induce further feeding activity. It was extraordinary. He seemed to have absolutely no concern with our activity. Remember, this is the type of Ray that perpetually freaked off as you approached them, by slowly wading or swimming gently towards them. Reggie and his fellow rays were all Thornback Rays, rays that do not have poison spines at the base of the tail. Rog and I have often thought back to that unique experience.”